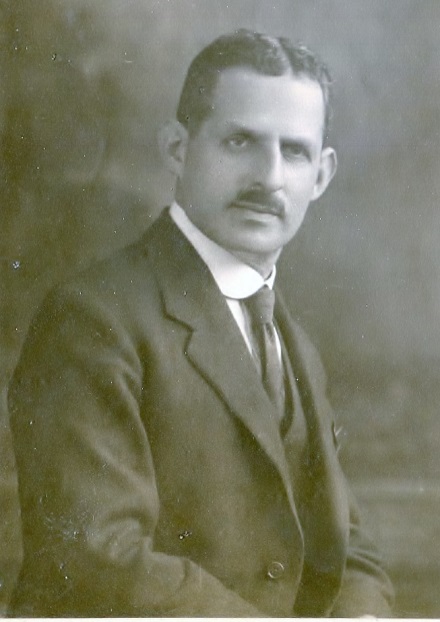

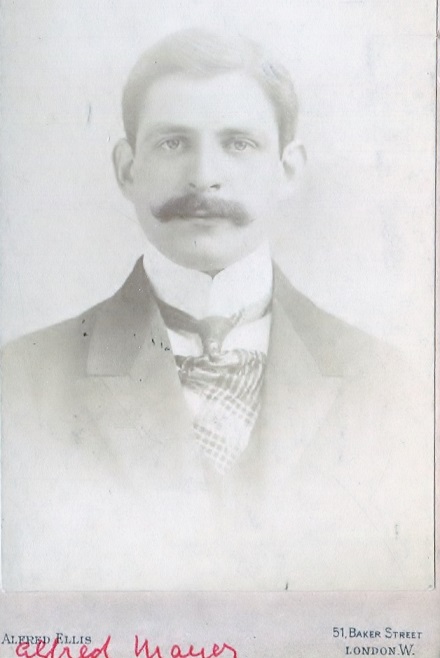

Alfred Mayer

My maternal grandfather Alfred Mayer (1872 - 1935) came to England from his home town of Ingelheim in his late teens. Alfred was naturalised as a British citizen in October 1900, aged 28 and a stockbroker’s clerk: he swore allegiance to “Her Majesty Queen Victoria, Her Heirs and Successors” just 3 months before the Queen’s death (January 1901). In the 1901 census Alfred and his brother Eugen (aged 20) were living at 136 Fellowes Road, Swiss Cottage, London: both brothers were described as clerks. (A Julius Mayer, aged 33, also a clerk, was living at the same address, but he is apparently unrelated.)

At the time of the 1911 census Alfred was aged 38 and living at the Windsor residential hotel in Lancaster Gate, London. His occupation now was Stockbroker’s Managing Clerk. Eugen, aged 30, was a boarder at 10 Leinster Square, Paddington; he was still German.

In the last quarter of 1912 Alfred Mayer married Evelina Schwarzschild in the Paddington District of London. Their first child, Ruth, was born on 28th September 1913; she and also my mother Nora (2nd December 1914) were born in their house at 5 Lymington Road, Hampstead.

I describe here the four week visit to London in April-May 1914 by Alfred Mayer’s father Heinrich and sister Helene, and that on arrival back in Ingelheim Heinrich wrote a loving letter dated 28th May 1914. Exactly a month after Heinrich Mayer wrote this letter, on 28th June 1914, Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo, and by 4th August Britain and Germany were at war.

Richard van Emden, in “Meeting the Enemy: The Human Face of the Great War” (2014, chap. 1: “The Age of Unreason”), gives a vivid and shocking account of how in 1914 it was possible within a few weeks for most Britons to accept that the “old enemy” France plus Tsarist Russia and Belgium were now our allies, and Germany were now our bitter enemies. Days after the declaration of war, Parliament passed the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) and the Aliens Restriction Act. The Press and most politicians soon whipped up hysteria against Germans generally, including those who had German ancestry (or name) but had lived for many years in England. All had to register, many were interned, and completely innocent people were attacked, their shops destroyed, sacked from their jobs and so made homeless.

Little is known about how the outbreak of World War I affected my mother’s German-born father Alfred Mayer and her maternal grandfather Jacob Schwarzschild. In 1917 Evelina was pregnant with her third child Henry (born in May 1918). Nora said: “they thought that because the war was on …it would be safer to go to Bournemouth, so my brother was born in Bournemouth.” After the war the family returned to Lymington Road and Joyce was born there in 1921.

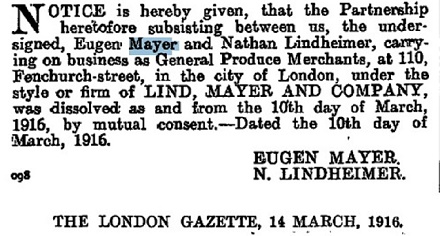

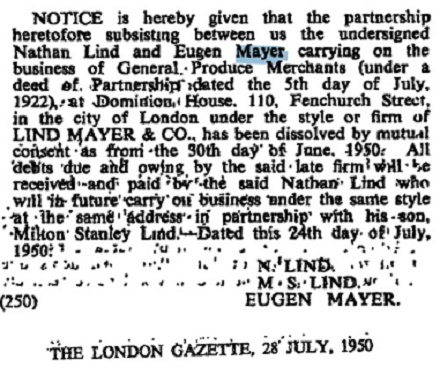

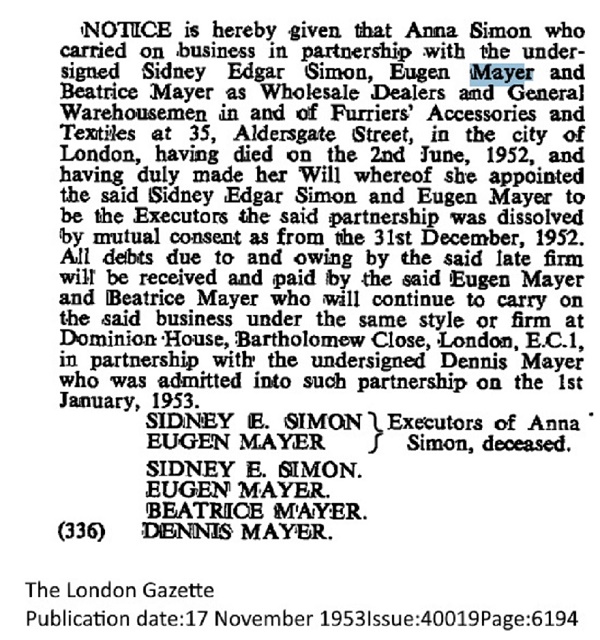

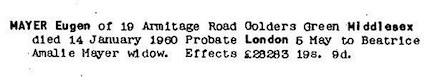

In 1909 Eugen Mayer was listed as a Commercial Agent at 59 Fenchurch Street in the City; he then went into a business partnership at 110 Fenchurch Street but in March 1916 this was dissolved. In 1922, after more than 20 years in London, Eugen applied for Naturalization as a British subject, a notification appearing in the Hampstead News, 27th April 1922. (Eugen was a lodger at 91 Greencroft Gardens, South Hampstead - about 15 minutes’ walk from Lymington Road, where Alfred and family lived.) Once naturalized Eugen resumed his pre-war business partnership which traded from 1922 until 1950 when Eugen retired aged 69.

In the 1921 census Alfred was “Managing Clerk” at Hartson & Co, Merchant Bankers in the City. There were two children’s nurses: Ada Jacob, aged 35, born in Dalston, East London, and Mabel Gealey, aged 20, born in Llanelli, South Wales. And there was a domestic servant, Joan Moger, aged 69, born in Hammersmith, London.

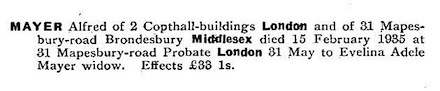

Alfred Mayer’s entry in the phone book for 1933 was still at Lymington Road, but in 1934 his address had changed to 31 Mapesbury Road, Kilburn, and it was here that Alfred died on February 15th 1935, aged 62. According to his probate his net estate was nil.

Nora said this about her father, Alfred Mayer:

He didn’t really speak with a German accent, perhaps a very slight one, for some things, but not really…. He had the most marvellous handwriting, and I think that, very often, handwriting shows character, and he did have a nice character. I did used to feel sorry for him because he was very clever, I think he was very clever at school, but he never earned much money, he never had a good job. You see, he came here with no degree, or any exams, and he worked, I think it was in merchant banking. He was not exactly a junior, but he never earned very much money. My mother came from a very well-off family. So he was sort of beholden to her, if you know what I mean….

I know that when my parents married, my mother had a marriage settlement. This is what they used to do in well-to-do families. I have a copy of it somewhere, and this marriage settlement - I used to feel very sorry for my father, because there were trustees, and it was all in stocks and shares, and the income went to my mother. So really, it didn’t matter that my father didn’t earn very much, because my mother had all the money, and I think that’s a bit demeaning on the man really….. I don’t think he ever earned much money, and I think it was hard on him, because if she wanted anything she could go to her father…. It was a happy marriage, but it was a different kind of a life.

My mother got the income all the time, she only got the income, not the capital. And what it said was, in this document, that on my mother’s death, all the shares should be sold, and the money should go equally between her children. With an exception: if any of the children had married a non-Jew, they would get nothing. Of course my youngest sister [Joyce] did marry a non-Jew, but we decided between ourselves that we weren’t going to let her get nothing, and so we let her be counted in - you can do that….

I told you that the capital went between the children, but if my father had still been alive, had he not died before my mother, he would have got nothing…. Although I missed him terribly, and I was very upset when he died, I thought it would have been terrible, because he would have had to ask his children for money. He didn’t have much of a job. And although there was all this money, he would have got nothing…

… He was only 62 when he died, he died of angina… You see in those days they didn’t have heart by-passes and they didn’t have the medication, and my mother had - she showed us once - a little sort of a file, and if he got a pain on the chest - whereas if I get it I put a tablet under my tongue - my mother used to break one of these under his nose and he would inhale it … So, 62, and she was 15 years younger, so she must have been in her forties when she was widowed with four children.. [Actually Evelina was 10 years younger than Alfred and was widowed at age 52.] And two of them still at school…

.. It was very very hard for her, after he died. You see, what happened was, he had an angina attack, he used to get them from time to time, and he had this angina attack, and they went to see a specialist, and he was only 62, and the specialist said he should go home and spend a week in bed, and then after a week, he’d be well enough to come back to the specialist. He was in bed, and he was doing fine, and my uncle Eugen, of course, was marvellous, he used to come every day, and if he didn’t come he’d ring, and so on. And I remember, he’d only been in bed then, this was about three days after he’d been to the specialist, and he seemed to be doing well, and I was working in a solicitor’s in the City, and my father’s office was in the City. And when I went in to see him before I went to work, he said, ‘I think, darling, if you don’t mind in your lunch hour, could you take my keys in for the safe, because I might be another few weeks off work, I don’t know how long, I think they might need the keys to the safe. So could you take the keys in for me?’ And so I said ‘of course’, and in the lunch hour I took the keys in, and I hadn’t been back in the office for long and couldn’t understand it because in those days you never got phone calls at work, and the phone had gone and they’d said ‘your mother’s on the phone, and wants to speak to you’. I went to the phone, and my mother said, ‘Daddy’s very ill, come home at once’. It was a Friday, I can tell you it was a Friday, because we used to have to work one Saturday in three or something, and I was supposed to work the next day, so I went straight into my boss and told him, and he said ‘go at once and don’t come in tomorrow’.

So I know it was a Friday. And all the way home - I had to go home on the Underground. We lived near Kilburn and Brondesbury station, Mapesbury Road, and all the way home I was worried, because I thought, he’s in agony, he’s in pain, and when I got home, my youngest sister Joyce, who was still at school, she and Henry were both still at school, and Joyce opened the door, and she said ‘Daddy’s dead’.

It was sudden like that. What happened, was that my mother was going shopping, and just before she went shopping my uncle phoned and said, ‘I’ll come this afternoon and see Alfred’. My mother went shopping, and when she came back, my father had the radio on, he liked to have the radio on a lot, and she went into the bedroom, and the wireless was still playing, and he’d taken his glasses off and he was holding them in his hand, and he was dead. I don’t know if she realised he was dead, or just unconscious. She phoned the doctor who came immediately, but he was dead.

Alfred’s grave in Willesden

You see, we didn’t own the house because my father would not buy a house on mortgage, because he was terribly old-fashioned. He didn’t really understand it. He said if you had a mortgage, you are borrowing money, and he wouldn’t borrow anything. You can’t imagine anyone saying that now. It’s silly really, because if you’re renting something, you’re paying money all the time, with nothing at the end. So, how much easier it would have been for my mother if he’d had a mortgage, and there are mortgages that if you die, that’s it, it’s the end of the mortgage.

…. [Evelina and Alfred] were happy, I mean I don’t think I ever saw them have an argument, not in front of us, but it was a happy atmosphere at home.

I’ll tell you something that was rather touching. In my father’s study, which I told you was on the ground floor, we had a canary. Did I tell you this story? And the canary sang most beautifully. And it hung over my father’s desk, and coming back from school, it was wonderful because I used to hear the canary singing as I came down the road, I could hear the canary singing. And after my father died, that bird never sang again. Now would you believe that a bird - he never sang again. We thought that he might be lonely, not that my father was there all the time, he was at work often, so we gave him to my cousin, Uncle Eugen’s son Dennis, because they had a canary, and we thought perhaps he was lonely, and if he had a companion, he might - but he never sang again. You’ve no idea what a beautiful way he used to sing when my father was alive. Would you believe that a bird would have a feeling like that? It’s true, it’s completely true.

Eugen Mayer - Nora’s favourite uncle

Eugen was born in 1881, so was 8 years younger than his brother Alfred.

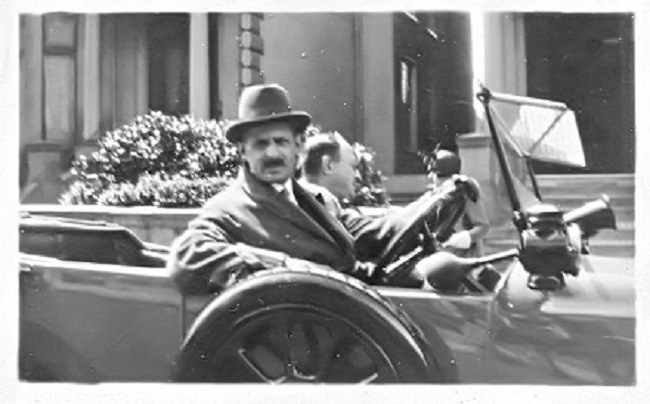

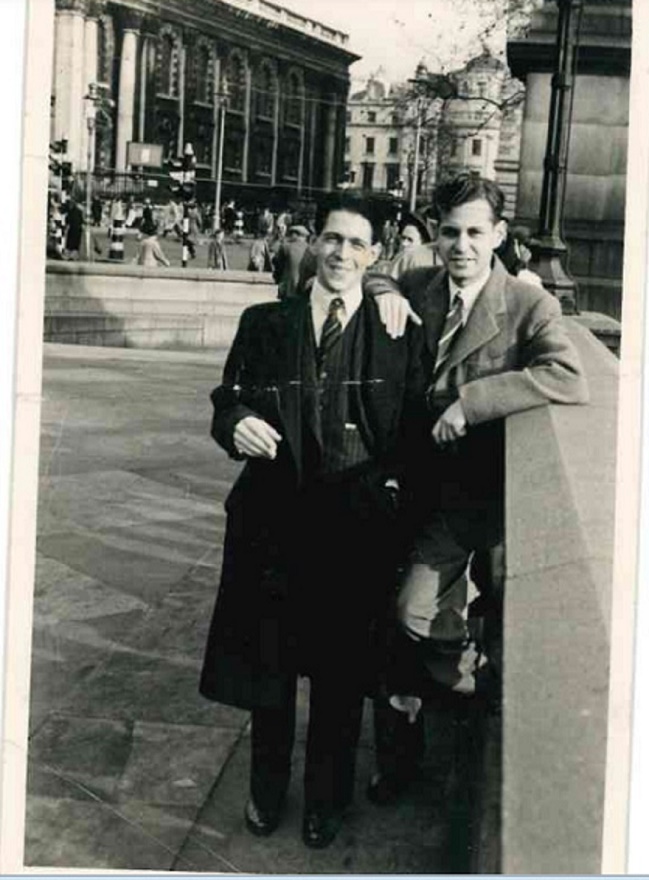

Eugen (left) and Alfred (right) in London

In the second quarter of 1925 the wedding took place in London of Eugen Mayer, aged 44, and Beatrice Amalie Simon, a 30-year-old German widow with a four-year-old daughter.

Beatrice was born in 1895 in Frankfurt. In February 1918 she was living in Charlottenburg, Berlin, with her parents Adolf Simon and Anna Strauss when she married lawyer Dr. Jur. Fritz Italiener; he had been born in 1886 in Berlin, his family having moved there from what was then Danzig in Germany and is now Gdańsk in Poland. Ruth Italiener, the daughter of Fritz and Beatrice, was born in Berlin in June 1921 and was aged two when her father died in 1923 aged 37.

When Eugen Mayer married Beatrice Italiener in North London he adopted the four-year-old Ruth (or “Ruthie”) and - according to Nora - treated her no differently from their own son, Dennis Henry Mayer, born in June 1926. (The middle name Henry was presumably after his late grandfather and Eugen’s father, Heinrich Mayer.)

From Aunt Helene’s photo album: Ruthie, Helene (visiting from Ingelheim), Dennis Mayer, and Ruthie’s grandfather Adolf Simon. London, c.1928

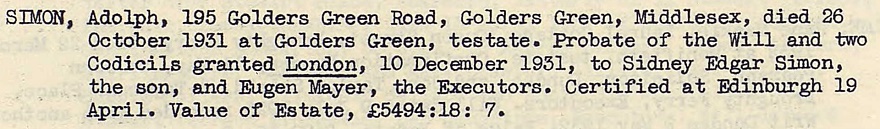

In 1931 Adolf Simon died in Golders Green, aged 74. His executors were Beatrice’s brother Sidney Edgar Simon (born 1891) and Eugen.

Nora remembered her uncle Eugen as a wonderful brother-in-law who, after the early death of his brother Hugo, travelled to Germany every year. Eugen saved both his nieces and his sister Helene from the holocaust by getting them over to England. For details see here

Nora said:

My favourite uncle, my father’s other brother, Eugen, who I absolutely loved, always used to call me Miss Mink, because apparently, when I was very young, I couldn’t say milk, so I always said mink…. He was the first person in the family on any side to have a car. I do remember that the very first time he came to see us with the car, and show it to us, he knocked our wall down.

In the 1939 Register Helene was included in the Mayer household at 19 Armitage Road, Golders Green. Ruthie, aged 18, was a typist and clerk. Eugen was a “produce merchant - East India trader”. But Eugen’s main business activity was a partnership with the Simons: Beatrice, her brother Sidney and mother Anna. They were “Wholesale Dealers and General Warehousemen in and of Furriers’ Accessories and Textiles” at 35 Aldersgate Street in the City. When Anna Simon died in June 1952 she was replaced by her grandson Dennis Mayer (aged 26) who joined his parents and uncle Sidney; in the future he inherited the whole business.

Dennis Mayer and his elder cousin Henry were great friends. Before Henry married in 1952 they met almost every Sunday and used to go on holiday together. Dennis (born 1926) was 8 years younger than his cousin Henry (born 1918) - just like their respective fathers Eugen and Alfred.

Henry (left) and Dennis (right)

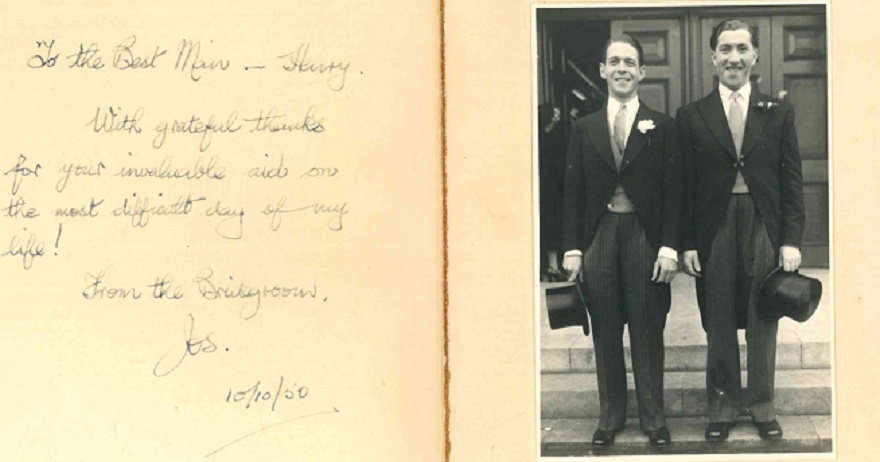

On 10th October 1950 Ruthie (aged 29) married Jos (Joshua) Barrett on his 42nd birthday, Henry Mayer serving as best man.

Ruthie moved to Jos’ house in Leeds, 6 Primley Park Road, Alwoodley, an area which is near the synagogue. Jos was born in Leeds in 1908 to Harry Barrett and Annie Cohen who had recently moved to England from Grodno, Belarus (Russian Empire) where their daughter Miriam had been born in 1902. Jos had two Leeds-born younger sisters, Dorothy (born 1911) and Iris (1915). After his parents died Jos lived in the Barrett family home with two of his sisters.

Eugen Mayer died in 1960 at the age of 79. Buried at Willesden.

When Auntie Bea died in 1975 around the time of her 80th birthday she was still living at 19 Armitage Road. Buried at Willesden. Their son Dennis Henry remained in the same house until he died, unmarried, in November 1991 aged 65.

Helene Mayer, the sister of Alfred and Eugen Mayer, had lived with Eugen and Bea in Golders Green until her death in 1946.

50 years later, in January 1996, Ruthie Barrett wrote to her cousin Ella Courts:

I have at last got down to sorting out some of the boxes from Armitage Road, containing old letters, photos, etc. I came across Auntie Helene’s photo album, and I enclose some of the pictures which I thought you might enjoy…

Helene Mayers’s photo album passed to Ella’s son Hugh Courts, and after his death in June 2019 to Keith Mayer, who kindly lent it to me in September 2019.

In 2005 we visited Ruthie and Jos in Leeds. They were living the same house - the Barrett family home - which Ruthie had moved to after their wedding in 1950. Jos was about 98, physically incapacitated but mentally 100%. He had read in his accountancy journal about “the oldest working accountant in Britain” and wrote to correct them because he was even older!

Ruthie was in her mid-80s, but while she was caring for Jos acted like someone 20 years younger. For our afternoon tea she prepared a dining table full of home-made treats. My only other experience of such a spread was that made by her mother, Auntie Bea: as a child in the 1950s we often visited Bea and my mother’s Uncle Eugen in Golders Green on a Sunday.

Jos Barrett died in June 2008, four months before his 100th birthday. Ruthie Barrett died in September 2010 when - aged 89 - she drove her car into the back of a stationary bus.

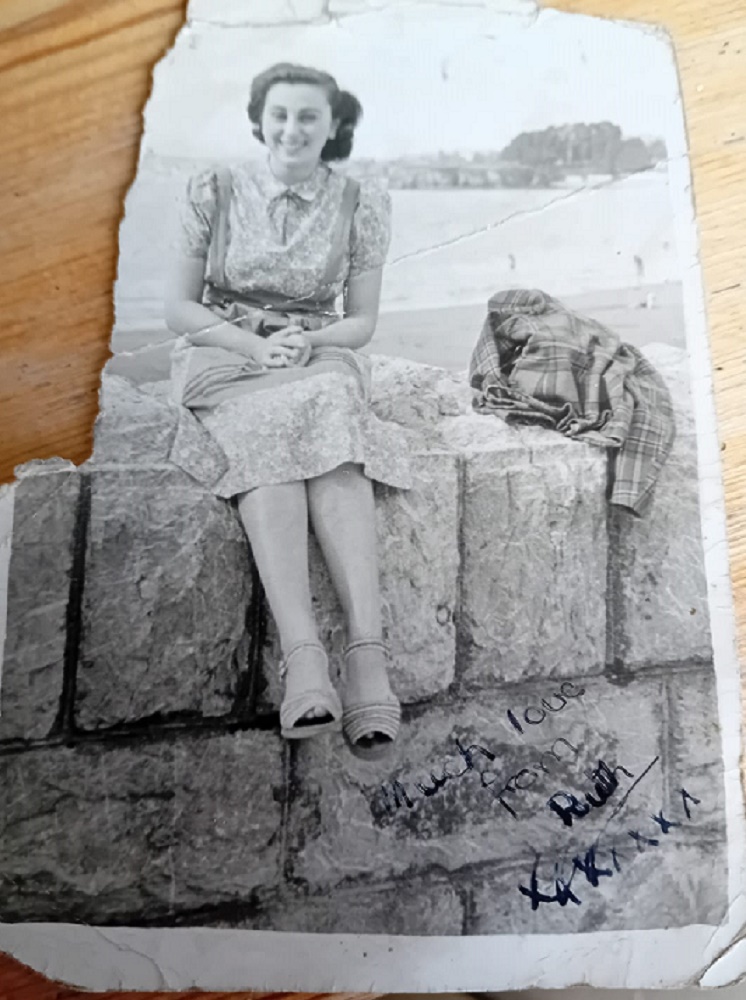

Going through his mother June’s photos after her death in 2024, Keith Mayer found “the only photo I’ve ever seen of Ruthie”.

The relatives of Auntie Bea’s first husband Fritz Italiener

Fritz Italiener had three younger sisters, all born in Berlin. Charlotte Margarete Italiener (born 1894) married Dr. med Hermann Spitz (born in 1885 in Salantai, Lithuania); he died in 1928 in Leipzig, aged 43. Else Adele Italiener (born 1896) married a fellow Berliner, Bernhard Epanianondes Berent and they emigrated to New York.

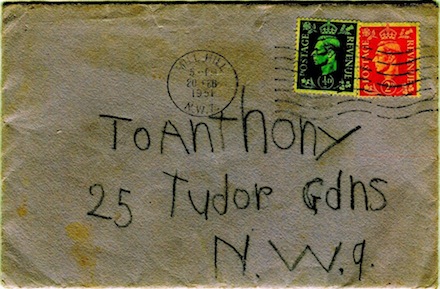

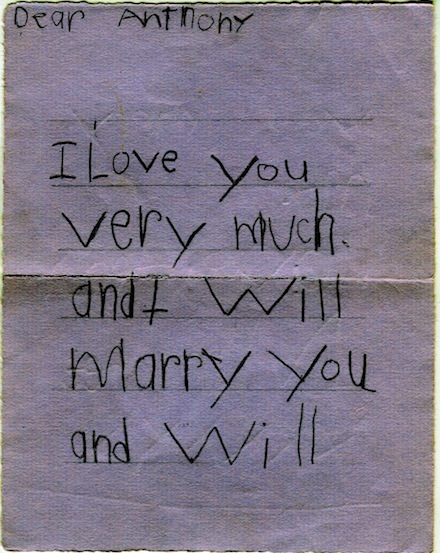

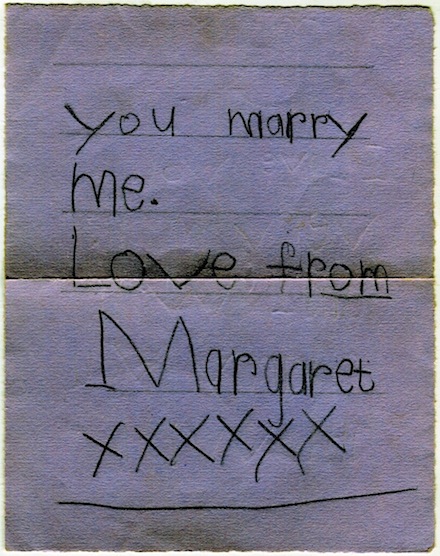

And Marie Elisabeth (born 1890) married Dr. med. Wilhelm Michaelis (born 1886 in Meseritz/Międzyrzecz, Germany now Poland). They emigrated to London and had three grand-daughters; one of them, Margaret, was about my age and sent me this letter in February 1951, when we were six.

Dr. med. Wilhelm Michaelis had a brother and a sister, also born in Meseritz. Leo (born 1882) died in December 1941 in the Minsk (Belarus) Ghetto aged 59. And Elisabeth Auguste (born 1892) married Willy Wreschinski (born 1887 in Pudewitz / Pobiedziska, Germany now Poland). Elisabeth, Willy and their daughter Liselotte Wreschinski died on 30 November 1941 in the Riga-Rumbula (Latvia) Ghetto, aged 49, 54, and 24. But their son Kurt Leopold Wreschinski, born in 1919, married Juliane Ilse Eisner (from Vienna) and they also emigrated to London, where they died in 1978 and 2014 respectively.

Special thanks to Keith Mayer for information and photos.

Page last updated 27 Aug 2025.