Heinrich Mayer

My great-grandfather Heinrich Mayer (1840 - 1916) owned a kosher butcher’s shop in Ingelheim am Rhein, a small town some 18km west of Mainz. He had the shop built in 1877 at Heimesgasse 14.

Heinrich Mayer married Kätschen Koppel, and they had four children: Alfred (born 1872), Hugo (1873), Helene (1878) and Eugen (1881).

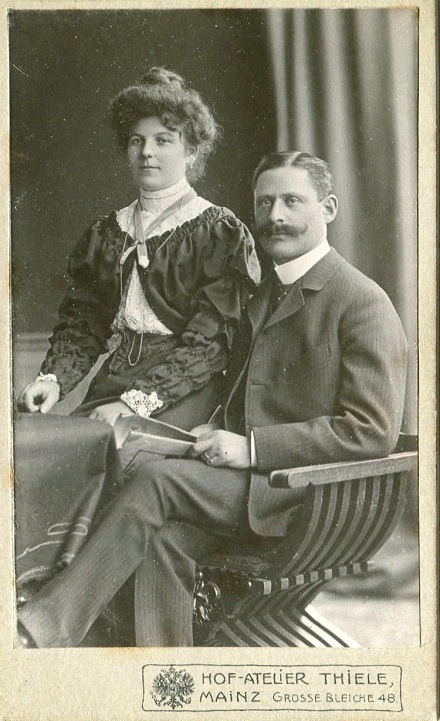

Heinrich and Kätschen

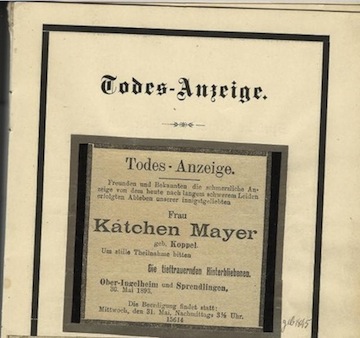

In 1893 Heinrich Mayer’s wife, my great-grandmother Kätschen Koppel, died aged 48.

My grandfather Alfred and Eugen moved to London as young men, while Hugo and Helene remained in Ingelheim. In 1904 Hugo took over his father Heinrich’s butcher’s shop.

Helene; and Hugo’s house in Ingelheim

In 1906 Hugo Mayer married Johanna Kapp, who was born in 1880 in Hechtsheim, a town 5 km south of Mainz and 23 km east of Ingelheim. Hugo and Johanna had two daughters, Käthe (born 1907) and Ella (born 1908).

Hugo and Johanna in 1905-6; Käthe and Ella in 1912-13

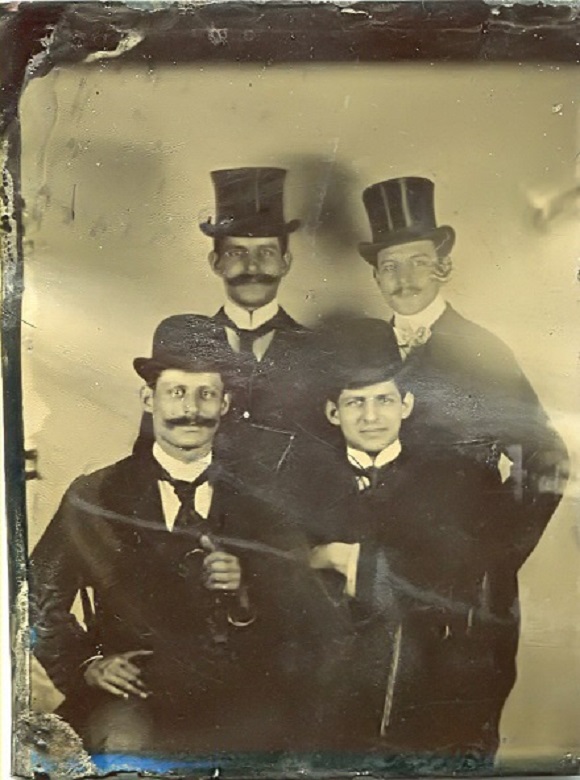

My grandfather Alfred Mayer emigrated to London some time around 1890. This picture was taken on the occasion of a visit to London by his brother Hugo.

The Mayer brothers - including Hugo - in London

Alfred Mayer married Evelina Scharzschild in 1912. Their first child was born in London on 28th September 1913 and named Ruth Kate (the Kate after her late grandmother Kätschen). At the end of April 1914 Heinrich and his daughter Helene travelled to England for a four week visit.

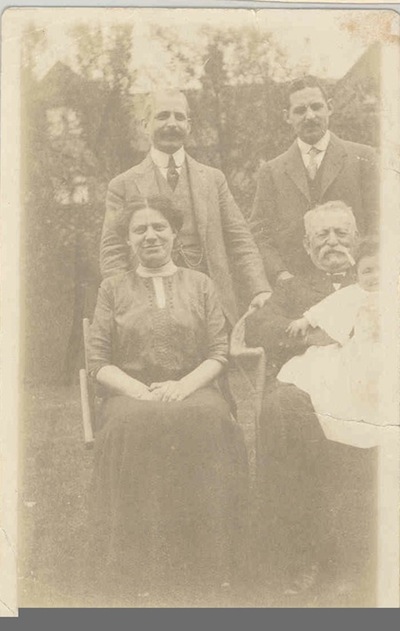

London, May 1914. Ruth aged 7 months with her grandfather Heinrich; Alfred, Eugen, Helene, Heinrich and Ruth

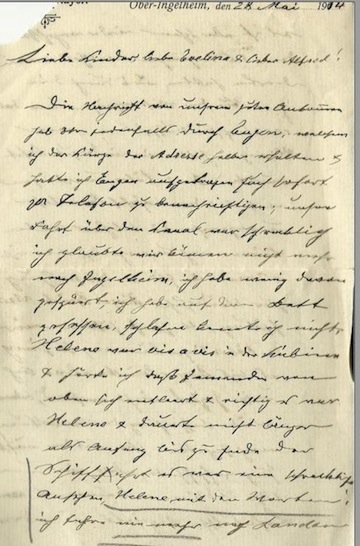

On arrival back in Ingelheim, Heinrich wrote a letter dated 28th May 1914. (See extract below,left. Very many thanks to Mrs Hanna Jones for the translation.)

… Our journey across the Channel was awful, I thought we would not see Ingelheim again. I saw little of the sea because I spent the whole journey in the toilet. Helene was opposite in the cabin, then I heard someone above being sick, it was Helene and it lasted from beginning to end of the crossing, it was horrendous to watch, Helene said ‘I will never travel to London again!’

But it is all forgotten now, the pleasure of feeling better lets us forget those miserable hours we endured ….. I must thank you for everything you did for us, your kindness. I can not write it all down, you know me as your father and I am not one for too many words. But I thank you from the bottom of my heart for everything, you dear Evelina especially, I found you to be as I have heard so often, and it gives me peace of mind, I count you to be one of my children. As I write to you, I have the picture of little Ruth on the table in front of me, do give her a kiss from me.

Love for you all and greetings to all relatives. From Grandfather Heinrich.

Exactly a month after Heinrich Mayer wrote this letter, on 28th June 1914, Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo, and by 4th August Britain and Germany were at war. My mother Nora was born on 2nd December 1914 but she never met her grandfather Heinrich.

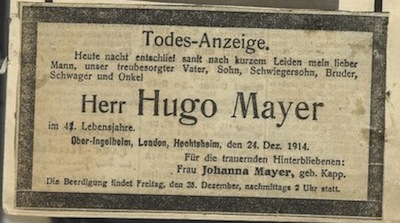

I discuss here the impact on those of German background living in England in August 1914. I can only guess at how the outbreak of war affected Germans such as the Mayers of Ingelheim who had close family in England. In any case, in December 1914 Hugo Mayer died aged 41 “after a short illness”, according to his death notice. However, on the Mainz Jewish Community web site it is recorded that Hugo’s death was a suicide.

Then in July 1916 Heinrich Mayer died aged 76.

After Hugo’s death in 1914 his widow Johanna was left to bring up the children - Käthe (aged 7) and Ella (aged 6) - and also manage the butcher’s shop.

In 1918 Käthe was 11. She appears in this photo with her class before they moved up to the gymnasium (equivalent to Secondary School in England).

Nora spoke of the extra difficulties for Johanna Mayer in the 1920s when the economic crisis hit Germany. She also said that Eugen was a very good brother-in-law and that he used to visit her every year and take presents for the girls. He also promised that when they grew up he would have them over to England and find them husbands. In the 1930s Eugen did indeed have Käthe stay with him and his wife Bea in Golders Green for a year. Later on Ella came to stay and a match-making with Ben Courts was successful! Ben Courts and Ella lived at 1 Halesbury Close, Stanmore, Middlesex. In 1935 they had a son Hugh who died in 2019 aged 84.

When Ella was expecting Hugh (1934-5) they managed to get Käthe (Ella’s elder sister) out of Germany. Earlier, when they were first married, Ella’s mother Johanna had visited London and they had tried to persuade her to stay with them as things were getting so bad in Germany. But as she told Nora at the time: “I’m not going to stay because they haven’t been married long and they haven’t got much money, and I wouldn’t be allowed to bring any money over, so I would be a burden on them.” So she went back to Ingelheim, and would die in the Holocaust. Nora’s cousin Ella said to her once, “we should have insisted more, and kept her here”.

Helene, the sister of Alfred and Eugen, was saved from the Nazis: she came to England and lived with Eugen and Bea in Golders Green. She never married, died in 1946 aged 68, and is buried in Willesden.

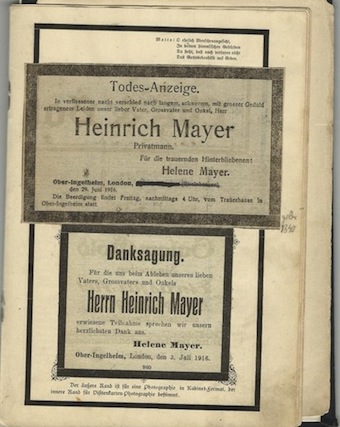

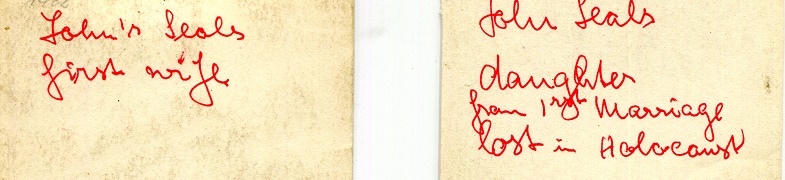

Käthe Mayer, born 1907, the elder daughter of Hugo and Johanna, worked as a nurse (or nursing assistant) in London during the war. In 1949, when she was aged 42, she married John Seal at the Edgware Synagogue.

Käthe Mayer in 1939-40; wedding to John Seal in 1949

John Seal was a widower. These photos, taken in Breslau (Warsaw), are of his first wife and daughter, who were both killed in the Holocaust.

In 1972 Käthe and John Seal were living at 67 Latymer Road, Edmonton, North London.

The Kapp family and the Hechtsheim Jews

Johanna Kapp, the widow of Hugo Mayer and mother of Käthe and Ella, had two younger brothers, David (born 1882) and Karl (1885). Karl was killed fighting for Germany in September 1916, aged 31. Less than a year later, Johanna’s mother Mathilde Schlösser died. Her father Emmanuel Kapp died in 1928. So David Kapp was Johanna’s only remaining close relative; a hunchback, he never married, and lived in Hechtsheim his whole life.

The Yad Vashem database confirms that in 1942 both Johanna (from Ingelheim) and her brother David (from Hechtsheim) were deported to Treblinka extermination camp.

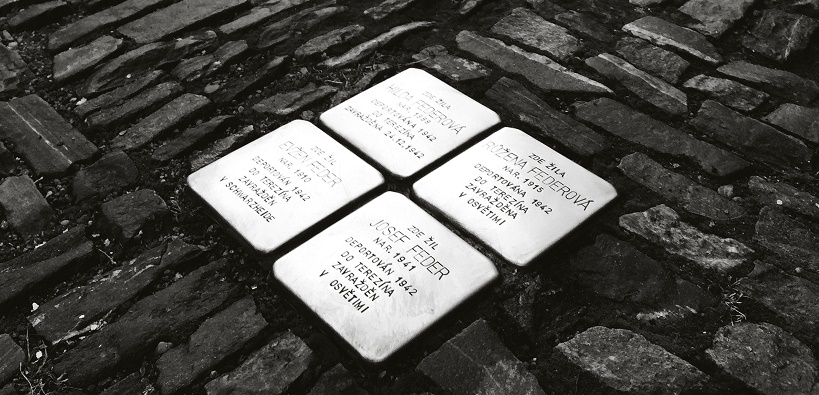

Johanna is memorialized on the Stolperstein site

And in June 2013 Stolpersteine were laid in Hechtsheim, including one at Alte Mainzer Straße 8 for David Kapp.

A Stolperstein is “a ten-centimetre (3.9 in) concrete cube bearing a brass plate inscribed with the name and life dates of victims of Nazi extermination or persecution. Literally, it means ‘stumbling stone’ and metaphorically ‘stumbling block’. The Stolpersteine project, initiated by the German artist Gunter Demnig in 1992. As of June 2023, 100,000 Stolpersteine have been laid, making the Stolpersteine project the world’s largest decentralized memorial.”

There is more about the Kapp family of Hechtsheim, including Johanna, and also about Heinrich and Hugo Mayer on the Mainz Jewish Community web site, where it is recorded that Hugo’s death in 1914 was not “after a short illness” (as per his death notice) but was suicide.

The implementation of the holocaust in Hechtsheim has been documented in extraordinary detail by Dr Anton Maria Keim (1928-2016), a native of the town, in his 1994 monograph “From Süssel Hechtsheim to David Kapp: The Hechtsheim Jews”.

David Kapp is still remembered by old Hechtsheimers…. On the decennial anniversary celebrations [in 1932], a special highpoint of village life, Hechtsheimers of the Jewish faith naturally and increasingly took part. In 1932, a year before Hitler’s ascension to power and the onset of the brutal period, Eduard Weiss and David Kapp were among the 37 who appeared in the group picture of the “Class of 1882”. There was no exclusion.

On the day after the pogrom night of November 1938 a jeering audience, including SA members, had the experience of watching David Kapp held out the second story window of his house across the street from the “Office of the NSDAP” and seeing the look of fear of the fifty-six year old man. Any indignation was expressed only behind the hand, so to say, in the family circle, or with friends of the same decent attitude. Yet David Kapp continued to live in the community in which he had been born …

The unassuming David Kapp, of stocky build, was respected by Hechtsheimers. Oldsters recall that in the summer of the first year of the war he st ill looked after his field and his garden … David Kapp is the last Hechtsheim Jew in the village. He had to experience every form of indignity. The village police were instructed by the acting mayor, at the direction of the state council, to keep an eye on David Kapp’s residence, and to supervise the implementation of the many annoyances imposed. The “Identification Label for the Residences of Jews” was ordered in 1942 by the chief of the security police - “with a paper Star of David conforming in shape and size to the identification patch prescribed in Sec. 1, Par. 2 of the referenced police regulation” - referring to the 1941 regulation regarding the wearingof he Star of David - “however in white…so that it will stand out better against the mostly brown doors.” Such discriminations were described bureaucratically right down to the details.

The district head wrote in the same connection to the mayors of Hechtsheim and Guntersblum on 21 Apr 1942 ordering implementation and periodic surveillance. The mayor, Steffan, added a handwritten notation dated 22 April 1942, “Hierold to check from time to time”. The order concerned the village policemen and related to David Kapp’s house at Adolf Hitler Strasse 8 (today Mainzer Strasse).

The many regulatory harassment’s of the third year of the Second World War included the confiscation of all fur garments and “collection of clothing pieces and old cloth from Jewish possession” (Letter of the state council of 5 June 1942 to the mayor of Hechtsheim). The village policeman noted “Done” on 12 June 1942. On 4 July 1942 a new letter concerning “Service to Jews by Barbers/Hairdressers”. “Under pain of state police action”, wrote the Reich Security Headquarters, service to Jews by barbers/hairdressers is forbidden from this time forward - whether in shops, residences or otherwise. Only service by Jewish barbers/hairdressers is excepted. Here, also, based on the one remaining Jew in Hechtsheim, the local policemen noted “Done”. The same for the order of 21 July 1942 providing, “that, according to a decree of the Reich Transportation Minister, the use by Jews of waiting rooms, buffets and other facilities of public transportation is forbidden.”

David Kapp appears as No. 787 in the 30 September 1942 deportation list of the Gestapo/Gestapo Office Darmstadt (“Transfer of Residence to the Generalouvernement”)…. In a file of Jewish residents of Hechtsheim turned up by chance in the preparation of this work, David Kapp’s name appears with a check mark, as well as a large handwritten entry “X address unknown 1942”. David Kapp was sacrificed to the organized mass murder, as were all the others on the deportation train, one of three that left the Güter (freight) railroad station of Mainz in 1942 with three thousand Jews bound for Piaski, “General Gouvernement” and Theresienstadt. He was the last of his family.

Boehringer Ingelheim and Dr Fritz Fischer

Today there is no Jewish population in Hechtsheim or Ingelheim. But Ingelheim is still home to Boehringer, founded in 1885 and the world’s largest private pharmaceutical company. Fritz Fischer (1912-2003) performed medical atrocities on inmates of the Ravensbrück concentration camp. In the 1947 Doctors’ Trial at Nuremberg Fischer was tried and convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity. He was sentenced to life imprisonment, but his sentence was commuted to 15 years and he was released in 1954 – after serving only 7 years. On his release Fischer “started a new career at the chemical company Boehringer in Ingelheim, where he stayed until his retirement.”

Special thanks to Keith Mayer for information and photos.

Page last updated 10 Sep 2025.